Wednesday, October 1, 2008

Remains of the day

Artist-turned-evidentiary photographer plies her trade at the county morgue.

By Ian M. LeBlanc

Forensic photographer Kelly Root turns the pages of a portfolio of evidence pictures at the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office. She’s surrounded by a group of students from a photography class she teaches at Oakland Community College. They’ve come on a blustery Saturday morning in March for a field trip, to get a glimpse of Root’s work at this, one of the nation’s busiest morgues.

Root hardly pauses as she skims through the images, rattling off details of each case. There are suicides, auto accidents, murders. The photos are startling, showing the carnage of gunshot wounds and the gore of autopsies in cold, unblinking clinical detail. The students look on, mute. But Root is unruffled.

Coming to a set of pictures that show a man lying on the floor and a close-up of a dead rodent, Root glances up. “This is interesting,” she says “This guy, he had a gun and he went to kill a mouse. He hit the mouse with the butt of the gun and it went off and killed him. So there’s the mouse in the corner.”

The students look at each other, apparently unsure of how to respond. Finally, one ventures timidly: “Did he get the mouse?”

Root’s lips compress into a hard line that’s neither a smile nor a grimace. Her response is deadpan. “Yeah,” she says, flipping to the next page, “he killed the mouse and himself at the same time.”

Root, one of her student guests comments, “doesn’t look like someone you’d expect to be working here.” Indeed, with her long blond hair, rosy complexion and delicately defined features, the 25-year-old looks more like a J. Crew model than the pasty, ghoulish mortuary worker of popular imagination.

Root doesn’t have the background you might expect of someone in her line of work either. She never planned to go into a forensic field; rather, she found her way to clinical photography from the distant world of the fine arts.

Growing up in a comfortable home in the Flint suburb of Flushing, this daughter of two GM assembly line workers was always interested in art. In high school she dabbled in painting and drawing before discovering photography. “I fell in love with the process,” she explains. “I loved watching images come up in the developer.” She was fascinated by the camera’s ability to capture and preserve a moment in time. It made her look at the things and people around her, she says, “in a whole new light.”

Photography quickly became her focus. “It was the only thing I was good at,” she says. After graduation, art school was the obvious choice. With her parents’ enthusiastic support she enrolled in the photography program at Detroit’s prestigious College for Creative Studies.

At CCS, Root’s interest in studying her surroundings led her to specialize in social documentary photography, a genre similar to photojournalism with its realism and emphasis on narrative. Working on undergraduate projects such as a study of street scenes on New York’s Lower East Side, or a series of portraits of twentysomething Detroiters, Root developed a rigorous, no-frills photographic style.

She prefers to shoot full-frame, meaning she doesn’t crop or otherwise manipulate her pictures after they’re printed. It’s a technique that emphasizes the photo’s content and demands a keen eye for storytelling and composition. “My photos are not always about the visual,” Root explains. “They’re more about the subject matter. It’s what the photo shows that matters most to me, not necessarily whether it looks like a piece of art.”

For her senior thesis project, Root chose to depict the process of embalming. Originally, she says, she wanted to document the experiences of people who work alongside death on a daily basis — doctors, medics, morticians, cops — and investigate how this contact affects their daily lives. “I got the best feedback from funeral homes, so I narrowed the scope of the project to focus on the process and environment of embalming,” she says.

She readily admits that it was a macabre subject for a photo thesis. But, she says, she wasn’t drawn to the topic out of simple morbid fascination. Instead, she chose to study embalming because it’s a completely ordinary, everyday occurrence that’s viewed as extraordinary. “It’s something that happens every day in every mortuary in Michigan, that will happen to most of us. Yet people don’t ever discuss it,” she explains. Her goal with the thesis, she continues, was to shed light on this otherwise hidden part of everyday life.

Another appeal of the project was the personal challenge it presented. “I got into that [thesis topic] because I wondered how I would react to the subject and how it would show in my photography,” she explains. “I wondered if I would shy away from it, if my photos would be from, like, 20 feet away. It made me go outside of my boundaries, both as a photographer and as a person.”

She quickly learned to adopt the morticians’ straightforward, matter-of-fact manner and attitude as well. “You know, at first it was uncomfortable. They [morticians] would make these morbid jokes and I was, like, ‘Oh, weird.’ But you adjust; when you work with it every day, it becomes part of [the experience],” she explains. “Maybe you don’t become totally comfortable with it, but you learn to accept it to a certain extent.”

The final product reflects this sense of acceptance. Though the project’s 27 images depict the preparation of the body in jarring, unflinching detail, they manage to overcome the initial repugnance of their subject matter and even lend it an unexpected and incongruous beauty.

In one shot, for example, a coil of rubber tubing turns gracefully over a corpse’s chest as a mortician inserts an IV of formaldehyde into a vein; in another, a woman lies on a table, her skin as luminescent as polished alabaster.

In all, it’s only the photos’ stark, somber beauty that makes them viewable. “The art quality of those photos was very important to me,” Root explains. “The composition, the light, the color — I wanted them to be as beautiful as possible in order to engage the viewer.”

Predictably, the thesis elicited much strong reaction. When it was displayed at her graduating class show, Root says, viewers were either powerfully drawn to it or powerfully repelled. “It was interesting to see people’s response. They would walk by, look at it, then look away. They didn’t know what to make of it. Some people would stop and take a closer look; others would keep going and avoid it.”

Comments in Root’s exhibit book illustrate this ambivalence. A note from a photo student praises her work as “intense” while another comment condemns it as “totally unnecessary and disrespectful.” Yet another viewer writes, “I’m getting cremated. Thanks for helping me come to this decision.” Someone else, who identifies himself as a photographer from a family of funeral directors, counters, “I would never disrespect the dead like you have.”

An especially offended viewer writes: “Your [sic] a sick son of a bitch go to hell! I hope I see you so I can kick your ass. Plus I hate you.”

Much to Root’s frustration, the ambivalence toward her work extended to some of the CCS faculty. Her thesis, she says, was placed in an out-of-the-way part of the exhibit area; she thinks the curators did this to avoid controversy.

Root’s friend and former CCS photography classmate Carrie Williams agrees. “Kelly was always one of the best in the photo program,” she says. “Everyone assumed she would be featured in the center gallery. When she wasn’t, we were all surprised. Everyone thought it was politics.”

Root was bemused by the negative response to her thesis — but wasn’t surprised. She admits that she was gratified to see viewers’ strong reactions, but insists that her aim wasn’t simply to be shocking. “Maybe it has shock value,” she says, “but there’s educational value too.”

She argues that objections stem mostly from people’s discomfort and unwillingness to talk — or even think — about death. Projects such as her thesis, she believes, are beneficial in that they compel viewers to ponder the frightening but inescapable fact of their own mortality. She contends that her photos do not compromise the dignity of her subjects. Rather, they show the truth of what happens to the body after death — a truth that may be disturbing, but that is nonetheless inevitable. “People don’t think about what happens to their loved ones after they die. They just blindly hand them over to the mortician. I wanted to show them what really goes on.”

While researching her thesis, Root became acquainted with Joseph Sopkowicz, the head forensic photographer at the Wayne County Medical Examiner’s Office. After her 2000 graduation, Root became a photography intern at the Warren Avenue office. At the end of her internship she began her present job as assistant forensic photographer. She is responsible for photographing cadavers that come through the office on weekends, holidays and when the chief photographer is away.

The duties of the forensic photographer go far beyond just snapping an identifying photo of the deceased. Standing in the viewing gallery that looks through a plate-glass window into the main exam room, Root explains to her students that the photographers also must physically prepare the bodies for photography. Preparation can include cleaning wounds to make them more visible to the camera and “breaking rigor” — forcing down limbs that have contracted in rigor mortis.

While preparing subjects for photography, the photographers sometimes discover wounds missed in the initial examination; Root gives the example of a recent case where she came across a gunshot wound in a subject’s ear that had been obscured by blood and passed over by the examining pathologist.

In other cases, such as with self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the head, the photographers may even have to reconstruct the remains of a corpse’s face to make an ID picture possible.

As Root details her duties, autopsy technicians wheel the day’s cases into main exam area. It’s a long, high-ceilinged room divided into several workspaces, each with a stainless steel exam table and sink.

Every surface shines pristine and antiseptic in the diffuse sunlight that comes through the skylight overhead. On a wall an autopsy technician has posted pictures of the cartoon characters Lilo and Stitch; in one of the workstations a small radio murmurs the sedate sounds of a smooth jazz station.

It’s a “slow day,” with only seven bodies to be examined. Root says she has worked days when the room was crowded with as many as 20. Among the cases on this Saturday morning are two suspected suicides, a teenager who was shot to death at a house party, and the skeletal remains of a child found in a vacant lot. The latter, arrayed on an exam table with the sheet and clothing with which the body was found, seem to pique the interest of the autopsy technicians. One picks up the skull with a gloved hand, examines what appears to be a fracture, and shakes her head.

“If it gets to be too much for you and you want to leave, there’s an exit around the corner,” Root says, indicating a side door.

Then she leaves her students in the gallery to join the team of autopsy technicians and pathologists, headed by chief medical examiner Dr. Sawait Kanluen. The team members, all clad in plastic aprons and gloves, move from table to table as Kanluen examines the corpses. Root listens attentively and jots down notes on a clipboard as the pathologist points out injuries and identifying features to be documented.

Minutes later, Root wheels the first case, one of the suspected suicides, into the photo room. It’s a cramped space that smells strongly of disinfectant. In a sink a faucet pours into an overflowing container of instruments; on an adjacent counter sits a large handheld digital camera and an array of forceps, rulers and other tools laid out on a tray.

Root’s manner is brisk and precise as she prepares to take the photos. She instructs her assistant, photo intern Nasreen Aziz, in a clipped, businesslike voice. She takes the identifying frontal shots, then she and Aziz flip the body to get a posterior view. They handle the corpse smoothly, confidently; neither seems to shrink from touching it. One of the students comments that it’s strange to see a human body move so stiffly; Root agrees, saying that the rigidity is a result of rigor mortis. As she shoots, she explains the technical details of the process to the students — the camera settings, how she frames the shots to best show injuries or important details, how she methodically changes her double set of gloves and disinfects the instruments and camera between each case.

She points to the rows of lights in the ceiling and smiles wryly. “Those used to be incandescent lights. I’m glad they changed them. It must’ve gotten really hot in here under all those.”

One of the students asks if Root ever feels uncomfortable in such a small room with the bodies. She laughs lightly. “Well,” she says, “when I first started, I wasn’t too thrilled about being in here alone with a case with the door shut. But I guess it doesn’t bother me now.”

With the shots finished, Root and Aziz peel off their gloves and aprons. Root puts the instruments in the sink to be disinfected, notes the shots on her clipboard, and returns the body to the main room.

In all, the shoot has taken only a few minutes. Root says that she tries to work as speedily as possible. “I just want things to move quickly and smoothly. I don’t want to hold anyone else up.” The photos, she says, must be completed before the autopsy is performed because they may be shown to the next of kin or used in court. “You really can’t do them after the autopsy. No one wants to see a photo of a person who’s been eviscerated.”

When it’s time to photograph the murdered teen, Root warns the students that the youth suffered a gunshot wound to the head. “If you don’t think you want to see that, you can go back to the photo office and wait for us,” she says. Several of the students nod uneasily and follow Aziz out of the exam room.

Root consults with one of the assistant medical examiners. He points out the multiple gunshot wounds to the youth’s head and chest. Apparently, the boy was shot to death some hours earlier after an argument over a rap song. The body, the doctor notes, is still slightly warm to the touch. Root shakes her head and comments on how young the boy looks. Then, following the doctor’s instructions, she slips a plastic block under the head, shaves the scalp at the site of the bullet’s entrance and takes a series of close-up shots.

One of the guests asks Root if she reacts differently to photographing victims of homicide, as opposed to natural deaths or suicides. Root ponders the question for a moment, then replies, “I guess I’m pretty detached from it. Sometimes I think about it, but for the most part I focus on my job. I didn’t see them suffer or die … it’s after the fact. I just focus on taking the picture the best way I can.”

Few cases shock her, Root continues. One of the few situations with the power to shake her detachment is when she sees a child who has died violently. “Sometimes when there’s a child, when I’m closing their eyes, I’ll say a little prayer, I’ll hope they didn’t suffer so much,” she says. “I know that they’re at peace now. So, yeah, I do think about it, but I realize that there’s nothing that can be done now. And my job is to make sure that there’s evidence to help catch and bring to justice whoever’s responsible for their death.”

The knowledge that her photography plays a part in the meting out of justice, Root explains later, is one of the most gratifying aspects of her job. She’s dismayed to hear that forensic photos don’t always make it into court. “They don’t like to show the pictures to juries,” she says. “They think they’re too much to handle.”

Nevertheless, Root believes that it’s important for people to see such images — for the same reason that it’s important for them to see depictions of procedures such as embalming. To her, it’s all part of being fully aware. Most people, she says, don’t realize how tenuous our grip on life really is, or how quickly and easily that grip can come undone.

“People die every day,” she says. “And sometimes they die so pointlessly, so stupidly.”

It is people’s inability to fathom their own mortality, and the mortality of others, she suggests, that too often leads to such senseless deaths.

She points to the example of the slain teen. “I just don’t understand it. People don’t think death can happen to them. They don’t understand the consequences of their actions. I mean, to shoot someone? Over a rap song?” She is incredulous. “Is it that they don’t understand the consequences of shooting someone, or that they just don’t [care]? Or are their lives worth so little to them?” She shakes her head.

“That’s what I want to show people,” she continues. “I want to show them consequences.”

Root’s small Hamtramck flat is a bright, cozy place: Old family portraits and photos from former classmates adorn the living room walls; a wall alcove houses a statue of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and re-creation; a jackalope head hangs near a window. Root sits cross-legged on a small armchair in front of a bookshelf stacked with photography monographs, novels and medical textbooks. She’s a gracious hostess, offering coffee and slices of poppy seed roll from a nearby Polish bakery. It’s a far cry from her brusque efficiency at work.

Still, even relaxed at home, Root is self-possessed and frank discussing herself and her work.

She admits that she has always had a rather dark worldview. Her experience at the morgue, she says, has only supported this. Seeing the terrible things that people do to each other has given her an insider’s glimpse of what “really” goes on in the world — “or at least in Wayne County,” she adds. It has also made her think that the world is a much weirder, scarier place than the average person realizes.

She emphasizes that it hasn’t made her trust people less. But it has made her more aware of her surroundings. She reads more into people’s actions and tries harder to divine their motives and intentions.

She has also become more conscious of her dealings with the opposite sex. The men that come through the morgue, she says, typically die of “straightforward” causes — accident, suicide, murder. They’re also more likely to be killed by strangers. Women, on the other hand, almost invariably suffer sexual violence, often at the hands of loved ones or acquaintances.

Predictably, she’s become more conscious of her own mortality. But, on the whole, she isn’t worried about finding herself on a table at the medical examiner’s office. “I don’t use drugs or sell drugs, I’m not in an abusive relationship, I don’t drive drunk or speed on icy roads,” she says, pointing out that, compared to most of the victims of untimely death that she sees in the morgue, she lives a low-risk lifestyle.

Root acknowledges that she is, to a certain extent, fascinated with the macabre. But it’s a normal fascination, she believes. “Everybody has that curiosity — they want to know how other people live, and how people die. They want to know about their compulsive little habits, eating batteries and metal, people who eat their hair. I just get to see the most negative aspects of that.”

Moreover, she emphasizes, “It makes me grateful for my life, my family. Like, my family’s not perfect — but it could be worse. Much worse.”

She doesn’t think that her experience at the morgue has changed her much. Her younger brother, David, agrees. He hasn’t noticed any great difference in his sister since she began working as a forensic photographer, he says by phone from Mt. Pleasant, where he’s a senior at Central Michigan University. The only noticeable change, he says, is that she’s grown more self-assured and confident than ever.

So confident, in fact, that she sometimes intimidates his friends on first introduction. “She’s older, attractive, smart,” he says. “I’ve had people say ‘Your sister scares me — I don’t know what to do around her. She’s too smart.’”

But, he says, his friends quickly realize that she is as personable and outgoing as she is intelligent.

Root knows that what she does isn’t for everyone — and she admits that on some days it can be too much for her. “Sometimes it doesn’t sit well. Sometimes you’ll get a really strong whiff of something you don’t want to smell. … It’s not the most pleasant thing to be around. I don’t know if I’d want to do it every day. Some days, when I have to photograph, like, eight cases, I’m like, ‘Man, I’m done.’”

But on the whole, she’s learned to accept most aspects of the job — even to see the work as normal. “Not that people are expendable, but I realize that people die every day. I’m going to die, you’re going to die. It’s part of living,” she says. “I think you can grow accustomed to anything.”

One of her coping mechanisms seems to be a healthy sense of humor. Root clearly doesn’t take herself too seriously. Her cell phone ringer, for instance, plays the theme from Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” — the organ riff that has become a scary-movie stereotype. And she makes no secret of her love of kitschy horror flicks, especially cornball thrillers such as Reanimator and Evil Dead.

She has no taste for more realistic depictions of gore in movies like The Silence of the Lambs, however. Those movies “don’t appeal to me,” she says. “I guess I don’t appreciate the novelty or shock the way someone else would. To me it’s just disturbing.”

She adds that the currently stylish, hyperrealistic carnage in films like Saving Private Ryan and on TV shows like “CSI” and “NYPD Blue” only adds to the public’s skewed view of death. “The concepts that they use in those shows are mostly accurate,” she explains, “but they’re still glamorized. They’re presented in this ‘gritty, realistic’ way, so people think they’re getting this glimpse of what really happens. But it’s still fake.”

Representing the truth has become more important than ever to Root. The rigorous accuracy demanded by her forensic work, she says, has increased her concern for clarity, detail and realism. At the morgue, she says, “there’s no room for my personal take on [the subjects].” Her pictures are strictly defined by their status as documents; ideally, the work of every clinical photographer should be identical.

Nevertheless, she often finds herself applying the rules of composition she learned in art school to her clinical work. Rather than simply taking a functional but uncomposed snapshot, she says, “I try to make sure everything is clean and neat and lined up and flawless. Because you want to concentrate on the characteristics of the [subject’s] injury and not how the photograph was taken.”

Root says she was “burnt out” on art photography after graduating from CCS. Dissatisfied with and uninspired by the Detroit art scene, she focused all her energies on her work at the Medical Examiner’s Office. It’s only recently that she’s begun to shoot for herself again.

At the same time that her fine arts training subtly influences her forensic work, her morgue experience has unsubtly influenced her technique and interests in art photography.

Root believes there’s a natural link between her art and forensic photography. Her aim in both of the two seemingly distant fields is the same: to tell a strong story in as direct a fashion as possible, with great attention to accuracy and detail.

“I guess I’ve got kind of an anal streak,” she says, then corrects herself. “No, wait. I shouldn’t say ‘anal.’ I should say ‘precise.’ It’s like ‘I’m a photography machine.’”

One current project depicts scenes, objects and textures from her past; its aim, she says, is to document these easily overlooked yet evocative aspects of her childhood. It includes environmental portraits of her family’s Flushing home, as well as meticulous studies of surfaces that are touchstones of her childhood — the wallpaper and carpet in her old bedroom, the polished grain of an old wooden door.

It’s all part of a desire to put herself into her pictures. “I’ve been taking pictures of other people for so long. Now I want to become part of the process, so I’m not just photographing other people, I’m photographing myself and putting myself in the same context.”

Root’s most ambitious current project is the Williams Root Gallery, the showcase that she and Carrie Williams will soon open in Hamtramck. Though both women are photographers, the gallery will be open to all media, not just photography. Its first show, planned to be a benefit for the Hamtramck police and fire departments, is tentatively scheduled for the end of the summer.

Williams, who lives downstairs from Root, is excited by the prospect of collaborating with her old friend and former classmate. Though the two have very different styles — Williams creates photo collages that depict fantastic or mythical beings and events and are a universe removed from Root’s gritty hyperrealism — Williams says that they have similar aesthetic senses and have long worked together. “Kelly is the first person I ask for advice. We always critique each other’s stuff — I know where she’s coming from,” she says.

Root is unsure where her work or her gallery will fit into the local photography scene. Speaking about the state of the arts in Detroit, she’s characteristically blunt. In Detroit, she says, too much attention is paid to “rock ’n’ roll and seedy underworld scenes,” while there is a dearth of high-concept, risky, well-crafted art. She and Williams hope to fill this void with their gallery.

“Hamtramck’s great,” Root says. “There’s really no pretension there. I come from a family of blue-collar workers; I feel at home here. I wouldn’t feel comfortable opening a gallery anywhere else.”

She takes a long view of the pertinence of her photography. “People always say, ‘Oh, it’s all been photographed before.’ But not in your time period. One thing about my pictures, they might not be so interesting now, but in 20 years they may be worth a lot more.” Besides, she adds, she’s in no rush: “Most photographers’ work isn’t even appreciated until after they’re dead.”

Ian M. LeBlanc is an editorial intern at Metro Times. E-mail letters@metrotimes.com.

http://metrotimes.com/editorial/story.asp?id=4947

Wednesday, September 24, 2008

Monday, September 22, 2008

Death becomes us

According to www.deathclock.com I will die on Tuesday 14 March 2051. At the time of writing that translates to 1 504 875 429 seconds left of living. But when my time comes will I die the death I want?

Perhaps the best way to die is to do so in a way that leaves the possibility of living again. Arrangements can be made at the Alcor Life Preservation Foundation (www.alcor.org) to cryopreserve your body—that is, to freeze it in liquid nitrogen for future resurrection. Once medical technology catches up, proponents of cryonics claim, it may be possible to have your suspended body revived, the cause of your death cured, and your aged and damaged cells repaired. Cryonics is touted as an extended form of artificial resuscitation: you wouldn't deny a paramedic resuscitating your heart after it stops beating, would you?

For those curious about death and the funeral industry, www.msprozac.zoovy.com (which is run by a webmaster battling advanced stage breast cancer) gives information on the dying process and how to plan for death. Death, after all, is a part of life, the site says, but this is mostly a commercial endeavour, and its embalming details and autopsy memorabilia may leave some people feeling queasy.

Advice on living wills (also known as advance directives) has proliferated on the web, much of it linked to the thriving funeral and insurance industries. From a healthcare perspective, the American Medical Association's online booklet (www.ama-assn.org/public/booklets/livgwill.htm) provides useful instruction to people wanting to document in advance their dying wishes and to designate an agent to execute treatment decisions if necessary. You can register your living will in the United States at www.uslivingwillregistry.com and in Canada at www.sentex.net/~lwr/index.html

Detail from a Day of the Dead costume, Mexico

Credit: KEN WELSH/BAL

The international site www.partingwishes.com has clever page wizards to help you securely document your preferences for burial or cremation, write a will, and design a future web based memorial. Online advice on creating your own funeral is hard to come by, but at www.allen-nichols.com/products.cfm you can buy a popular workbook. Any memorial service is unlikely to come cheap for your family (http://observer.guardian.co.uk/Print/0,3858,4681030,00.html). For the bereaved who are planning funerals and juggling the various financial, legal, and practical decisions that accompany the death of a loved one, the Vancouver based www.funeralswithlove.com is a gentle, compassionate resource.

The death websites at www.selfgrowth.com/archive/death-websites.html range from the bizarre to the sublime. Of these, death-dying.com offers perhaps the broadest range of content on death, dying, bereavement, and caregiving, mostly geared towards non-professionals. Unlike other sites, it includes sections on dealing with sudden deaths such as suicide and murder. Self assessment tools, chat rooms, book reviews, question and answer forums with experts, and a personalised email service of grief support are offered, and its content appears to be updated regularly. A series of provocative personal views—some touching, others ranting—might provide comfort to those experiencing the rollercoaster of grief.

A good death is emphasised at Growth House (www.growthhouse.org), an educational site for healthcare professionals and consumers on life threatening illness and care at the end of life. Special sections on the death of infants and children and on pregnancy loss have comprehensive advice that will probably help people. But its professional content is thin. The section on quality improvement, for example, lists a series of organisations rather than examples of best practices or clinical guidance. Perhaps its best feature is its hosting of the inter-institutional collaborating network on end of life care, an online international group of palliative care organisations.

Palliative Care Matters (www.pallmed.net), founded by a consultant in Wales, provides news, scientific articles, drug advisories, job postings, conference announcements, and regular updates on governmental happenings for healthcare professionals working in palliative care in the United Kingdom. Forums are also hosted. The site is detailed and user friendly, with a "quick update" link that lists content posted within the previous seven days.

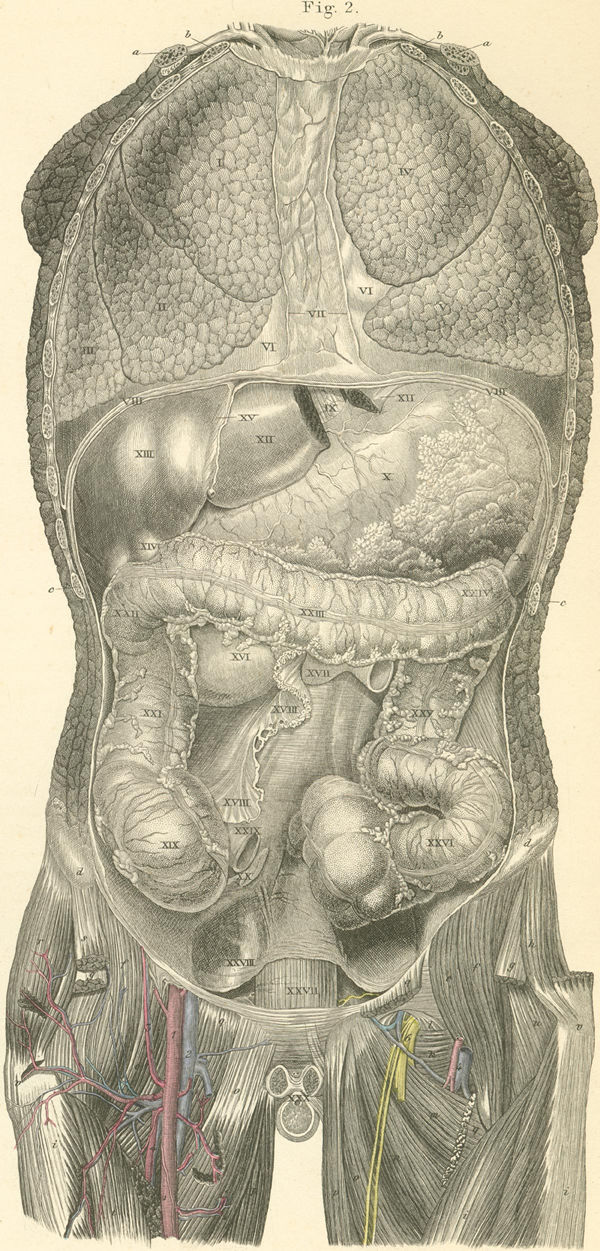

The National Library of Medicine site (www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/hmd.html) has an outstanding history of medicine collection including Physician Struggling with Death For Life. Photogravure by Ivo Saliger

Credit: NLM

Celebrating the dearly departed, www.mexconnect.com/mex_/feature/daydeadindex.html provides a fascinating, if frenetic, series of photo and journalistic accounts of Mexico's Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. The festivities involve such customs as macabre adornments and lively reunions at family burial plots, chocolate skulls and skeletons, fireworks, and seasonal flowers such as cempazuchiles (marigolds) and barro de obispo (cockscomb) that serve as offerings to the dead. www.darwinawards.com slyly commemorates individuals who eliminate themselves "in an extraordinarily idiotic way" from the gene pool.

If you wish to seek solace in the words expressed in the moments before death, choose from the last words of famous people (www.geocities.com/Athens/Acropolis/6537/index.htm) or the rather sprightly Japanese jisei (death poems) at www.samurai-archives.com/deathq.html

Jocalyn Clark, editorial registrar

BMJ jclark@bmj.com

http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/327/7408/231

Perhaps the best way to die is to do so in a way that leaves the possibility of living again. Arrangements can be made at the Alcor Life Preservation Foundation (www.alcor.org) to cryopreserve your body—that is, to freeze it in liquid nitrogen for future resurrection. Once medical technology catches up, proponents of cryonics claim, it may be possible to have your suspended body revived, the cause of your death cured, and your aged and damaged cells repaired. Cryonics is touted as an extended form of artificial resuscitation: you wouldn't deny a paramedic resuscitating your heart after it stops beating, would you?

For those curious about death and the funeral industry, www.msprozac.zoovy.com (which is run by a webmaster battling advanced stage breast cancer) gives information on the dying process and how to plan for death. Death, after all, is a part of life, the site says, but this is mostly a commercial endeavour, and its embalming details and autopsy memorabilia may leave some people feeling queasy.

Advice on living wills (also known as advance directives) has proliferated on the web, much of it linked to the thriving funeral and insurance industries. From a healthcare perspective, the American Medical Association's online booklet (www.ama-assn.org/public/booklets/livgwill.htm) provides useful instruction to people wanting to document in advance their dying wishes and to designate an agent to execute treatment decisions if necessary. You can register your living will in the United States at www.uslivingwillregistry.com and in Canada at www.sentex.net/~lwr/index.html

Detail from a Day of the Dead costume, Mexico

Credit: KEN WELSH/BAL

The international site www.partingwishes.com has clever page wizards to help you securely document your preferences for burial or cremation, write a will, and design a future web based memorial. Online advice on creating your own funeral is hard to come by, but at www.allen-nichols.com/products.cfm you can buy a popular workbook. Any memorial service is unlikely to come cheap for your family (http://observer.guardian.co.uk/Print/0,3858,4681030,00.html). For the bereaved who are planning funerals and juggling the various financial, legal, and practical decisions that accompany the death of a loved one, the Vancouver based www.funeralswithlove.com is a gentle, compassionate resource.

The death websites at www.selfgrowth.com/archive/death-websites.html range from the bizarre to the sublime. Of these, death-dying.com offers perhaps the broadest range of content on death, dying, bereavement, and caregiving, mostly geared towards non-professionals. Unlike other sites, it includes sections on dealing with sudden deaths such as suicide and murder. Self assessment tools, chat rooms, book reviews, question and answer forums with experts, and a personalised email service of grief support are offered, and its content appears to be updated regularly. A series of provocative personal views—some touching, others ranting—might provide comfort to those experiencing the rollercoaster of grief.

A good death is emphasised at Growth House (www.growthhouse.org), an educational site for healthcare professionals and consumers on life threatening illness and care at the end of life. Special sections on the death of infants and children and on pregnancy loss have comprehensive advice that will probably help people. But its professional content is thin. The section on quality improvement, for example, lists a series of organisations rather than examples of best practices or clinical guidance. Perhaps its best feature is its hosting of the inter-institutional collaborating network on end of life care, an online international group of palliative care organisations.

Palliative Care Matters (www.pallmed.net), founded by a consultant in Wales, provides news, scientific articles, drug advisories, job postings, conference announcements, and regular updates on governmental happenings for healthcare professionals working in palliative care in the United Kingdom. Forums are also hosted. The site is detailed and user friendly, with a "quick update" link that lists content posted within the previous seven days.

The National Library of Medicine site (www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/hmd.html) has an outstanding history of medicine collection including Physician Struggling with Death For Life. Photogravure by Ivo Saliger

Credit: NLM

Celebrating the dearly departed, www.mexconnect.com/mex_/feature/daydeadindex.html provides a fascinating, if frenetic, series of photo and journalistic accounts of Mexico's Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. The festivities involve such customs as macabre adornments and lively reunions at family burial plots, chocolate skulls and skeletons, fireworks, and seasonal flowers such as cempazuchiles (marigolds) and barro de obispo (cockscomb) that serve as offerings to the dead. www.darwinawards.com slyly commemorates individuals who eliminate themselves "in an extraordinarily idiotic way" from the gene pool.

If you wish to seek solace in the words expressed in the moments before death, choose from the last words of famous people (www.geocities.com/Athens/Acropolis/6537/index.htm) or the rather sprightly Japanese jisei (death poems) at www.samurai-archives.com/deathq.html

Jocalyn Clark, editorial registrar

BMJ jclark@bmj.com

http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/327/7408/231

Incurably Alive: Woman Faces Death with a Sense of Humor

A cancer patient has turned her own impending death into a business, www.bluelips.com, that deals in the subject of death.

(PRWEB) May 8, 2005 -- In 1999, Toni Riss was diagnosed with an aggressive breast cancer. The cancer, in fact, had spread to her bone and she was given a prognosis of 2-5 years. When Ms. Riss read her medical chart, it said "incurable." She was so incensed that she made her doctor change the wording to "incurably alive."

But this is only the beginning of her story. Ms. Riss is helping to change attitudes and is saving lives through her website http://bluelips.com. When Ms. Riss went to make her funeral arrangements she found the funeral home evasive and abrupt in their treatment of her. She was hurried along and asked to make decisions quickly and even commit to an expensive funeral contract. She refused and when she tried to ask questions about what the funeral home was going to do to her body when she died, she was told "no one ever asks those kinds of questions."

As a result of her experience, she started a website called "Bluelips" where the average consumer can purchase items such as an embalming or autopsy video, anatomical chocolate, post mortem collectibles and other oddities. Her descriptions in many cases are full of humor. She donates over 25% of the profits to breast cancer research.

Ms. Riss has made unpaid appearances on a Penn and Teller show and is interviewed in the documentary "Flight From Death." Her website has been featured in the book "Internet Babylon" where she received a three-page review. As controversial as her website is, she has a number of fans rooting for her as is evidenced by over 600,000 visitiors to her site since its inception.

Ms. Riss spends as much time as she can educating others about advanced breast cancer, but also how to protect themselves from unscrupulous funeral directors. Ms. Riss is called "the new Jessica Mitford." The late Jessica Mitford wrote the stunning expose "The American Way of Death" about the funeral industry years ago. Ms. Riss, being a fan of Ms. Mitford's, feels that the site honors her work, just in a different medium.

"Jessica was my hero growing up. She taught us to stand up for ourselves and to ask questions. All that I learned from her I have put to use in my every day life so that I question doctors, lawyers and any professional to whom I am entrusting my well being to," says Ms. Riss.

Bluelips.com is an unusual place to shop, with an unusual history behind its existence. Bluelips.com has also raised the consciousness of the public -- and it has done so with a sense of humor.

http://www.prweb.com/releases/2005/05/prweb237031.htm

(PRWEB) May 8, 2005 -- In 1999, Toni Riss was diagnosed with an aggressive breast cancer. The cancer, in fact, had spread to her bone and she was given a prognosis of 2-5 years. When Ms. Riss read her medical chart, it said "incurable." She was so incensed that she made her doctor change the wording to "incurably alive."

But this is only the beginning of her story. Ms. Riss is helping to change attitudes and is saving lives through her website http://bluelips.com. When Ms. Riss went to make her funeral arrangements she found the funeral home evasive and abrupt in their treatment of her. She was hurried along and asked to make decisions quickly and even commit to an expensive funeral contract. She refused and when she tried to ask questions about what the funeral home was going to do to her body when she died, she was told "no one ever asks those kinds of questions."

As a result of her experience, she started a website called "Bluelips" where the average consumer can purchase items such as an embalming or autopsy video, anatomical chocolate, post mortem collectibles and other oddities. Her descriptions in many cases are full of humor. She donates over 25% of the profits to breast cancer research.

Ms. Riss has made unpaid appearances on a Penn and Teller show and is interviewed in the documentary "Flight From Death." Her website has been featured in the book "Internet Babylon" where she received a three-page review. As controversial as her website is, she has a number of fans rooting for her as is evidenced by over 600,000 visitiors to her site since its inception.

Ms. Riss spends as much time as she can educating others about advanced breast cancer, but also how to protect themselves from unscrupulous funeral directors. Ms. Riss is called "the new Jessica Mitford." The late Jessica Mitford wrote the stunning expose "The American Way of Death" about the funeral industry years ago. Ms. Riss, being a fan of Ms. Mitford's, feels that the site honors her work, just in a different medium.

"Jessica was my hero growing up. She taught us to stand up for ourselves and to ask questions. All that I learned from her I have put to use in my every day life so that I question doctors, lawyers and any professional to whom I am entrusting my well being to," says Ms. Riss.

Bluelips.com is an unusual place to shop, with an unusual history behind its existence. Bluelips.com has also raised the consciousness of the public -- and it has done so with a sense of humor.

http://www.prweb.com/releases/2005/05/prweb237031.htm

how a sewing machine works

The English cabinetmaker Thomas Saint received the first patent for a sewing machine in 1790. Elias Howe, credited as the inventor of the sewing machine, designed and patented his creation in 1846. Howe was employed at a machine shop in Boston and was trying to support his family. A friend helped him financially while he perfected his invention, which also produced a lock stitch by using an eye-pointed needle and a bobbin that carried the second thread.

Here is an amazing animation, after the jump, as to how sewing machines work.

Howe tried to market his machine in England, but, while he was overseas, others copied his invention. When he returned in 1849, he was again backed financially while he sued the other companies for patent infringement. By 1854, he had won the suits, thus also establishing the sewing machine as a landmark device in the evolution of patent law.

Chief among Howe’s competitors was Isaac M. Singer, an inventor, actor, and mechanic who modified a poor design developed by others and obtained his own patent in 1851. His design featured an overhanging arm that positioned the needle over a flat table so the cloth could be worked under the bar in any direction. So many patents for assorted features of sewing machines had been issued by the early 1850s that a “patent pool” was established by four manufacturers so the rights of the pooled patents could be purchased. Howe benefited from this by earning royalties on his patents; Singer, in partnership with Edward Clark, merged the best of the pooled inventions and became the largest producer of sewing machines in the world by 1860. Massive orders for Civil War uniforms created a huge demand for the machines in the 1860s, and the patent pool made Howe and Singer the first millionaire inventors in the world.

Improvements to the sewing machine continued into the 1850s. Allen B. Wilson, an American cabinetmaker, devised two significant features, the rotary hook shuttle and four-motion (up, down, back, and forward) feed of fabric through the machine. Singer modified his invention until his death in 1875 and obtained many other patents for improvements and new features. As Howe revolutionized the patent world, Singer made great strides in merchandising. Through installment purchase plans, credit, a repair service, and a trade-in policy, Singer introduced the sewing machine to many homes and established sales techniques that were adopted by salesmen from other industries.

The sewing machine changed the face of industry by creating the new field of ready-to-wear clothing. Improvements to the carpeting industry, bookbinding, the boot and shoe trade, hosiery manufacture, and upholstery and furniture making multiplied with the application of the industrial sewing machine. Industrial machines used the swing-needle or zigzag stitch before 1900, although it took many years for this stitch to be adapted to the home machine. Electric sewing machines were first introduced by Singer in 1889. Modern electronic devices use computer technology to create buttonholes, embroidery, overcast seams, blind stitching, and an array of decorative stitches.

http://www.impactlab.com/2008/03/19/how-a-sewing-machine-works/

Sunday, September 21, 2008

http://www.embalming.net/faq.htm

Why do we need embalming?

The purpose of embalming is to preserve a dead human body from natural decomposition and to also restore a natural appearance. It is required whenever a body will be presented at a public viewing, when a body must be held without refrigeration, or whenever a body will be shipped on an airline. Embalming, along with other restorative techniques, can restore a body that has been ravaged by disease, decomposition, trauma, etc. to a more familiar and pleasing appearance. Also, embalming provides some safety benefit to the public as it significantly disinfects a body.

What happens if the body isn't embalmed?

Immediately upon death, various enzymes and bacteria, such as clostridium perfringens, begin to break down a corpse. Many of these bacteria produce toxins that break down tissue and gasses that cause extreme swelling. Very delicate skin and open "sores" called skin slip develops. Refrigeration slows down this process as does embalming, so the sooner the embalming is done, the better. Embalming chemicals work to kill these bacteria and arrest the enzymes.

Why formaldehyde?

Formaldehyde is used because it coagulates protein (what muscle and skin are made of), making the protein firm and more sturdy. Formaldehyde is also a powerful disinfectant.

Do they remove the internal organs?

No. If the internal organs are removed it is done if the body is autopsied by the medical examiner. It's actually a lot more work for an embalmer to embalm an autopsied or "posted" case (posted = post mortem examination), because he or she cannot use the circulatory system as normal. The embalmer would have to inject each arm, each leg, and the head separately and then treat and pack the empty torso and abdomen.

How long does embalming last?

Even if perfectly embalmed, every body will sooner or later decompose. How soon depends on the quality of embalming, burial container, burial location (such as mausoleum or in-ground).

One funeral director I know exhumed a body 5 years after it was buried. The remains were well preserved except for some mold growing on the face. However, if given enough time, these remains will eventually break down.

Placing the casket in an aboveground mausoleum accelerates the decomposition process, including the production of decomposition gasses, due to the summertime heat. Because of this, there is much debate about "sealer caskets," caskets that have a rubber gasket around the lid. According to Batesville Casket Company, their "Monoseal" casket keeps out moisture and vermin while allowing decomposition gasses to escape. However, there are stories of some caskets actually exploding due to the buildup of these gases. This article gives a little better insight into this disturbing subject.

Some of you may be wondering about Lenin and Stalin, bodies of Russian leaders who have been kept for decades without decay. These bodies were regularly given "refresher" treatments and kept in a very controlled environment. But, they too someday will most likely deteriorate.

I want to become an embalmer. Where do I go for more information?

If you live in the United States, visit this website: "Complete List of Accredited Mortuary Schools" - The site contains information for mortuary schools throughout the United States. You can also try US College Search for listings by state. For more specific information, contact one or more of the mortuary schools listed. If you live in the United Kingdom, visit the British Institute of Embalmers and click on "Education" for a list of accredited embalming tutors.

Where do you practise embalming?

I do not practise embalming. I have never been to mortuary school. The information on this website is the result of research including videos, reading, and speaking with funeral industry professionals.

My family and I were horrified when we saw our loved one in the casket. What can we do?

You should first speak with the embalmer who worked on your loved one. Do not be afraid to ask questions. They should have the answer to just about anything you ask. Although not required, many embalmers make and keep embalming logs that detail the condition of the body before, during, and after embalming as well as procedures and chemicals used. If something seems shady, then contact the state's funeral service board - all states (to my knowledge) have one. They can help you if you feel there was negligence on the part of the embalmer.

How bad can a body look and still be restored to a natural appearance?

Much of it depends on the skill of the embalmer. Also you cannot expect embalmers to be miracle workers. I was told by one embalmer that at least 2/3 of a face needs to be intact in order to do an accurate restoration. Things such as edema (swelling caused by fluids) can be reduced and even elliminated by chemicals and procedures. Even many burned and decomposed cases can be restored.

The purpose of embalming is to preserve a dead human body from natural decomposition and to also restore a natural appearance. It is required whenever a body will be presented at a public viewing, when a body must be held without refrigeration, or whenever a body will be shipped on an airline. Embalming, along with other restorative techniques, can restore a body that has been ravaged by disease, decomposition, trauma, etc. to a more familiar and pleasing appearance. Also, embalming provides some safety benefit to the public as it significantly disinfects a body.

What happens if the body isn't embalmed?

Immediately upon death, various enzymes and bacteria, such as clostridium perfringens, begin to break down a corpse. Many of these bacteria produce toxins that break down tissue and gasses that cause extreme swelling. Very delicate skin and open "sores" called skin slip develops. Refrigeration slows down this process as does embalming, so the sooner the embalming is done, the better. Embalming chemicals work to kill these bacteria and arrest the enzymes.

Why formaldehyde?

Formaldehyde is used because it coagulates protein (what muscle and skin are made of), making the protein firm and more sturdy. Formaldehyde is also a powerful disinfectant.

Do they remove the internal organs?

No. If the internal organs are removed it is done if the body is autopsied by the medical examiner. It's actually a lot more work for an embalmer to embalm an autopsied or "posted" case (posted = post mortem examination), because he or she cannot use the circulatory system as normal. The embalmer would have to inject each arm, each leg, and the head separately and then treat and pack the empty torso and abdomen.

How long does embalming last?

Even if perfectly embalmed, every body will sooner or later decompose. How soon depends on the quality of embalming, burial container, burial location (such as mausoleum or in-ground).

One funeral director I know exhumed a body 5 years after it was buried. The remains were well preserved except for some mold growing on the face. However, if given enough time, these remains will eventually break down.

Placing the casket in an aboveground mausoleum accelerates the decomposition process, including the production of decomposition gasses, due to the summertime heat. Because of this, there is much debate about "sealer caskets," caskets that have a rubber gasket around the lid. According to Batesville Casket Company, their "Monoseal" casket keeps out moisture and vermin while allowing decomposition gasses to escape. However, there are stories of some caskets actually exploding due to the buildup of these gases. This article gives a little better insight into this disturbing subject.

Some of you may be wondering about Lenin and Stalin, bodies of Russian leaders who have been kept for decades without decay. These bodies were regularly given "refresher" treatments and kept in a very controlled environment. But, they too someday will most likely deteriorate.

I want to become an embalmer. Where do I go for more information?

If you live in the United States, visit this website: "Complete List of Accredited Mortuary Schools" - The site contains information for mortuary schools throughout the United States. You can also try US College Search for listings by state. For more specific information, contact one or more of the mortuary schools listed. If you live in the United Kingdom, visit the British Institute of Embalmers and click on "Education" for a list of accredited embalming tutors.

Where do you practise embalming?

I do not practise embalming. I have never been to mortuary school. The information on this website is the result of research including videos, reading, and speaking with funeral industry professionals.

My family and I were horrified when we saw our loved one in the casket. What can we do?

You should first speak with the embalmer who worked on your loved one. Do not be afraid to ask questions. They should have the answer to just about anything you ask. Although not required, many embalmers make and keep embalming logs that detail the condition of the body before, during, and after embalming as well as procedures and chemicals used. If something seems shady, then contact the state's funeral service board - all states (to my knowledge) have one. They can help you if you feel there was negligence on the part of the embalmer.

How bad can a body look and still be restored to a natural appearance?

Much of it depends on the skill of the embalmer. Also you cannot expect embalmers to be miracle workers. I was told by one embalmer that at least 2/3 of a face needs to be intact in order to do an accurate restoration. Things such as edema (swelling caused by fluids) can be reduced and even elliminated by chemicals and procedures. Even many burned and decomposed cases can be restored.

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

The ultimate green burial: no embalming, no casket

Funeral firms call it "natural'' and environmentally friendly. It is also plugged as "cost effective.''

By TAMARA EL-KHOURY, Times Staff Writer

Published January 6, 2008

The owner of Eternal Rest Cemetery in Dunedin, Charles Scalisi III, stands in the cemetery with an electronic device that enables the user to locate the correct burial spots of deceased.

DUNEDIN

Now there's a way for the truly environmentally conscious to go green even after death.

Charles Scalisi III, the owner of Eternal Rest Memories Park and Funeral Home is offering what he calls Green Burial, where the deceased is placed directly in a grave sans casket. Scalisi also offers biodegradable caskets.

Scalisi said this method is natural and cost effective. It also cuts many costs associated with a traditional funeral, including embalming $445 and a casket ($1,000 and up).

He's been working on the concept for a year and found that the use of a casket or vault is not required by law. Neither is embalming.

"Right now the community, society, is squeezed on spending a lot on a funeral," Scalisi said.

A green burial space costs $1,495. Spaces are two deep, meaning one person is buried in the bottom space, while the top space can hold either another person, the cremated remains of 10 people or a memorial tree. The owner of a bottom space can buy the top space for a reduced price.

An electric marker is buried with each grave. Using a device similar to what is used to find underground utility poles, Scalisi can scan an area and find the exact location of an individual's remains.

No one has been buried yet in the area of the cemetery Scalisi calls "Greenland." He is just introducing the concept to the public but thinks it will take off.

"Everybody I've spoken to about it loves it," he said.

Diana Marr, director of the state's Division of Funeral Cemetery and Consumer Services said she has read about green burial in trade magazines. The department doesn't keep track of how many cemeteries in the state offer green burial as an option but Marr said there's no rules prohibiting the practice.

Glendale Memorial Nature Preserve in the Florida Panhandle has been offering green burials since 2002.

Since then, 20 people have been buried there, said John Wilkerson, who formed the nonprofit organization with his brother. They inherited the land, which now consists of 350 acres of natural preserve and 70 acres of cemetery.

"Everything is a cycle and the cycle of nonsustainable funerals has peaked and is on its way down," Wilkerson said.

He said he believes the practice of green burials will become more popular for several reasons: it's better for the environment, more affordable, more spiritual and appeals to the growing aversion to embalming.

"We have people coming here from Tampa, from Miami and that doesn't make sense," Wilkerson said. "They should have their own local green cemeteries. There should be one every 100 miles all across the United States."

Tamara El-Khoury can be reached at tel-khoury@sptimes.com or (727) 445-4181.

To learn more:

Green burials

To find out more about green burials at Eternal Rest Memories Park and Funeral Home in Dunedin visit www.greenburialusa.com.

Learn more about the Glendale Nature Preserve at www.glendalenaturepreserve.org.

By the numbers:

22,500 cemeteries across the United States

Each year they bury approximately:

827,060 gallons of embalming fluid

90,272 tons of steel

2,700 tons of copper and bronze

30-million-plus board feet of hardwoods from caskets

1,636,000 tons of reinforced concrete

14,000 tons of steel from vaults

Compiled from statistics by Casket and Funeral Association of America, Cremation Association of North America, Doric Inc., the Rainforest Action Network, and Mary Woodsen, Pre-Posthumous Society

[Last modified January 5, 2008, 22:35:04]

http://www.sptimes.com/2008/01/06/Northpinellas/The_ultimate_green_bu.shtml

Monday, September 8, 2008

Autonomic nervous system

The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning

By Maurice Lamm

Autopsy and Embalming

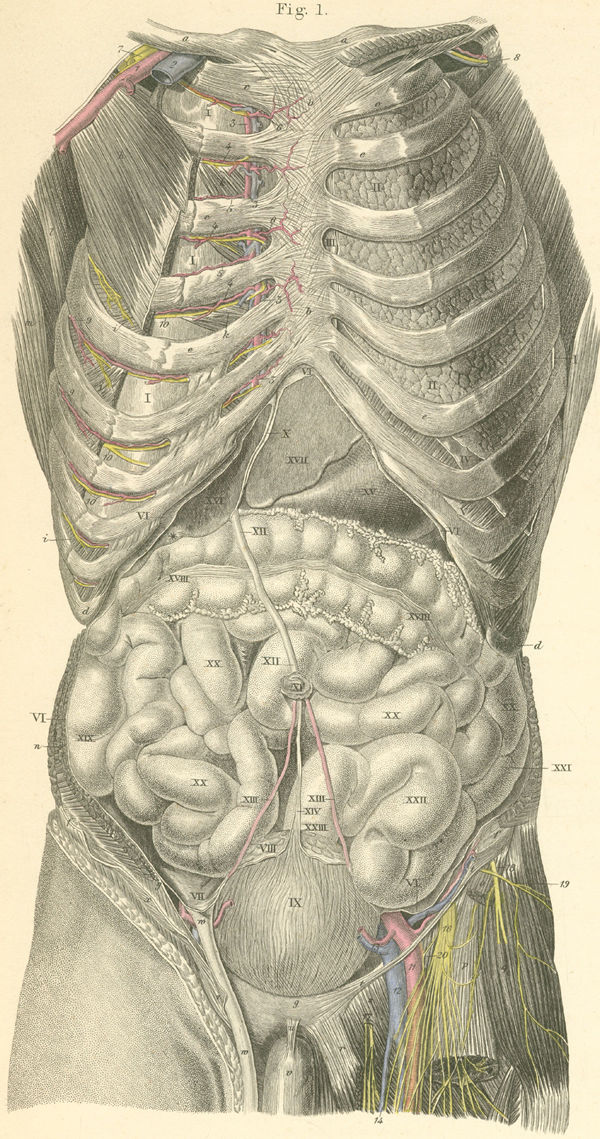

Post-mortem examinations often include autopsies. The purpose of this dissection of the corpse is to establish the cause of death and the pathological processes involved. The pathologist strives to acquire reliable information concerning the nature and cause of the disease, and perhaps to investigate the medical procedures used on the patient. The initial autopsy incision opens the entire body in a "Y" shape. It begins below one shoulder, continues under the breasts, and extends up to the corresponding point under the other shoulder. This incision is then joined by another in the midline extending down toward the pubis, to complete the "Y." The scalp incision begins under one ear, extends across the top of the scalp and ends behind the other ear. The organs are removed and studied to the extent of each individual autopsy requirement. It should be noted that the standard autopsy permit form in the Autopsy Manual published by the United Hospital Fund of New York includes, as a matter of course, authorization for "the retention of such parts and tissues as the hospital staff may consider necessary for diagnosis."

Consent from next of kin is required for autopsy. Such consent may be given by the legal custodian of the body who is responsible for the burial, usually the husband or the wife. If there are more than one "next of kin" (and the interpretation of that phrase is elastic) and controversy arises, the hospital may forego autopsy or elect the most amenable relative as "the" next of kin.

In truth, however, it may be fairly surmised that the cause of death is accurately known in most cases, and only rarely is this a medical mystery. From experience with modern medical procedure, it is evident that autopsies are most frequently recommended in order to enable medical students and internes to study and practice by dissection and observation of the corpse. Many articles in medical journals have asserted that recent progress in patho-physiological science has made possible the reliable determination of cause of death without an autopsy. It is now held by many authorities that, with some exceptions, autopsies are no longer considered as vital as they once were.

Nonetheless, it appears that the percentage of autopsies is still considered one of the best indices of the standard of medical practice in hospitals. For this reason the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Hospitals requires the maintenance of a satisfactory autopsy percentage. The United Hospital Fund standard manual urges obtaining consent in every possible case. "Indeed," says the Autopsy Manual, "when permission is not obtained, the physicians in attendance should be expected to account reasonably for such failure."

Hospital administrative staffs outdo themselves in perfecting techniques of extracting consent. Arguments are offered to counter typical family objections-some of these often untrue, and far below the high ethical practice the public has come to expect of the medical profession. One such argument often advanced is, "There are on record authoritative statements from religious leaders of all faiths indicating that nowhere is there any justification for opposition to autopsies on religious grounds." It is unfortunate that the religious sensibilities of traditional Jews should be so cavalierly dismissed by such misleading statements. Although there are notable exceptions to the rule, there is definite religious objection to autopsy.

Even though the motive of medical study is a worthy one, Jewish tradition forcefully rejects autopsies performed for teaching medical students, because this violates a higher principle: that of mutilating the body of the deceased. Jewish law is governed by several basic principles:

First, man was created in the image of God, and in death his body still retains the unity of that image. One may not do violence to the human form even when the breath of life has expired. Judaism demands respect for the total man, his body as well as his soul. The worthiness of the whole of man may not be compromised even in death.

Second, the dissection of the body, for reasons that are not urgent and directly applicable to specific existing medical cases, is considered a matter of shame and gross dishonor. As he was born, so does the deceased deserve to be laid to rest: tenderly and lovingly, not scientifically and dispassionately, as though he were an impersonal object of some experiment. The holiness of the human being demands that we do not tamper with his person.

Third, we have no permission to use his body without his own express desire that it be used, and even then it is questionable whether the person himself may volunteer to mutilate the image in which he was created. Certainly, where the deceased in his lifetime gave no express permission, even his children have no rights of possession over his body. Thus, we have no moral right, except for the cases to be mentioned, to use the body of the deceased by offering it as an object for study.

Autopsies are indeed valid in certain unusual cases, and these are exceptions to the general prohibition. While the possibilities of religiously-permitted autopsies are listed below, a competent rabbinic authority must be consulted in every case:

A) Cases which fall under the jurisdiction of governmental authorities. Here the decision must be made by the Medical Examiner. For convenience and clarity, such hospital cases can be divided into two groups

GROUP 1. Cases with impelling legal implications in which an autopsy is usually performed by the Medical Examiner, and in which permission for autopsy is never requested by the hospital physician.

Examples of such cases are:

a. Death by homicide or suspicion of homicide.

b. Death by suicide or suspicion of suicide.

c. Death due solely to accidental injury. d. Death resulting from abortion.

e. Death from poisoning or suspected poisoning, including bacterial food poisoning.

GROUP 2. Cases in which the Medical Examiner may decide that it is not necessary for him to do an autopsy as part of his post-mortem investigation.

Examples of such cases are:

a. Death occurring during or immediately following diagnostic, therapeutic, surgical, and anesthetic procedures, or following untoward reactions to medication.

b. Death occurring in an unusual or peculiar manner, or when the patient was unattended by a physician, or following coma or convulsive seizure the cause of which is not evident.

c. Death resulting from chronic alcoholism, without manifestation of trauma.

d. Death in which a traumatic injury was only contributory, and in which the trauma did not arise out of negligence, assault, or arson, such as a fracture of the neck resulting from a fall at home and contributing to the death of an elderly person, or accidental burns occurring in the home.

B) Cases of hereditary diseases, where autopsy may serve to safeguard the health of survivors.

C) If another known person is suffering from a similar deadly disease, and an autopsy is considered by competent medical authority as possibly able to yield information vital to his health.

D) In cases where the deceased specifically stipulated that an autopsy be performed there has been much rabbinic disagreement. The circumstances must be investigated on an individual basis, and only an informed, highly competent religious authority may decide.

Even in cases where the rabbis have permitted the postmortem, they have always insisted that:

Any part of the body that is removed must thereafter be buried with the body, and that it be returned to the Chevra Kadisha for this purpose as soon as possible.

The medical dissection must be performed with utmost respect for the deceased, and not handled lightly by insensitive personnel.

Because these matters are of great religious concern, questions on post-mortem examinations must be answered by a competent rabbi who is aware of both the medical requirements and the demands of the tradition. In addition, some forms of autopsy, such as the removal of fluid or blood only, or the insertion of an electric needle, may be considered permissible in many instances. The decision to perform an autopsy should not be made by the physician, no matter how close he is to the family and how reputable a doctor he may be. The prohibition is of a moral-religious nature, and permission should be obtained from an authority on religious law after consultation with medical authorities.

Embalming

The procedure of embalming was instituted in ancient times to preserve the remains of the deceased. Preservation was desired for many reasons:

1. For sanitation purposes--the assumption being that the fresh remains were a hazard to health;

2. For sentimental reasons--the family feeling that it wanted to prevent deterioration of the physical body as a comforting illusion that the deceased still lived; and

3. For presentability--to avoid visible signs of decay while the deceased was being viewed by the public prior to the funeral service.

It is worthwhile to analyze the three reasons in order to determine their validity today. First, however, it should be clear that there is no state law in the United States that requires the deceased to be embalmed, except when it is to be carried by public conveyance for long distances.

Is there a sanitary purpose for embalming? From all available evidence, the unembalmed body presents no health hazard, even though the deceased may have died from a communicable disease. Dr. Jesse Can, quoted in The American Way of Death by Jessica Mitford, indicates that there is no legitimate sanitation reason for embalming the deceased for a funeral service under normal circumstances.

Do reasons of respect and love warrant embalming to preserve the remains as long as possible? Many relatives feel, naturally, that they wish to hold on to their beloved in his human form as long as possible. If this is the major purpose of the embalming, several points should be taken into consideration:

1. The body will keep, under normal conditions, for 24 hours, unless it has been dissected. If it was kept refrigerated, as is the standard procedure, it will unquestionably keep until after the funeral service.

2. The body must eventually decompose in the grave. Under optimum conditions, even were the embalming fluids to retard the deterioration of the outer form for considerable length of time, reliable reports of reinterments indicate that the remains soon become sickening to behold and totally unnatural, as a consequence of the embalming.

3. Sentiment should attach to the person as he lived his life, as he appeared during the years of good health, not to the corpse as it appears while entombed. The deceased himself undoubtedly would want his loved ones to remember him as he was during the peak of his lifetime.

The prohibition of embalming for the purpose of viewing the deceased is considered in a separate chapter later in the book.

In the entire procedure of embalming today there is great confusion. There is not general public knowledge as to the methods of embalming, and certainly very little is known of "restoring," or cosmetology, a term used by the funeral industry for propping, primping, berouging, and dressing the remains to be placed on view. There is little doubt that if the family were aware of the procedures they might be too horrified to request it. A detailed description is available in Jessica Mitford's The American Way of Death.

The guiding religious ideal in regard to embalming is that a person upon his demise should be laid to rest naturally. There should be no mutilation of his body, no tampering with his remains, and no handling of the body other than for the religious purification. Disturbance of the inner organs, sometimes required during the embalming procedure, is strictly prohibited as a desecration of the image of God. The deceased can in no wise benefit from this procedure. So important is this principle, that Jewish law prohibits the embalming of a person even where he has specifically willed it.

It is not a sign of respect to make lifelike a person whom God has taken from life. The motive for embalming may be the desire to make of the funeral a last gift or a lasting memorial, but surely mourners must realize that this gift and this memorial are only illusory. The art of the embalmer is the art of complete denial. Embalming seeks to create an illusion, and to the extent that it succeeds, it only hinders the mourner from recovering from his grief. It is, on the contrary, an extreme dishonor to disturb the peace in which a person should be permitted to rest eternally.

It is indeed paradoxical that Western man, nourished on the Christian concept of the sinfulness of the body, which is considered the prison of the soul, should, in death, seek to adorn it and make it beautiful. Surely, the emphasis on the body in the funeral service serves to weaken the spiritual primacy and traditional religious emphasis on the soul.

There are, however, several exceptions to the general prohibition of embalming. These are:

1. When a lengthy delay in the funeral service becomes mandatory.

2. When burial is to take place overseas.

3. When governmental authority demands it.

In these cases, all required because of health regulations, Jewish law permits certain forms of embalming. Rabbinic authority must be consulted to determine the permissibility of embalming and the method to be used. One method frequently used is freezing. This is an excellent modem, clean method of preserving, also recommended by Dr. Jesse Carr, Chief of Pathology at San Francisco General Hospital.

The injection of preservative fluid, without the removal of the organs of the body, frequently has been used. If the blood has been released from the veins it should be collected in a receptacle, which should then be buried with the body. Bloodied clothes, worn by those killed accidentally or by violence, should be buried with the body. The blood is considered part of the human being and even in death they are not to be separated. As time goes on, and our knowledge of chemistry advances, other methods may be developed which Jewish law may consider legitimate.

The foregoing paragraphs are only general guidelines, and do not offer specific dispensation. Specific cases require individual attention and special permission from competent religious authority.

By Maurice Lamm More articles... |

The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning by Rabbi Maurice Lamm. To purchase the book click here.

The content on this page is copyrighted by the author, publisher and/or Chabad.org, and is produced by Chabad.org. If you enjoyed this article, we encourage you to distribute it further, provided that you comply with the copyright policy.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chabad.org · A Division of the Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center

In everlasting memory of Chabad.org's founder, Rabbi Yosef Y. Kazen

© 2001-2008 Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center

http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/281548/jewish/Autopsy-and-Embalming.htm

Autopsy and Embalming

Post-mortem examinations often include autopsies. The purpose of this dissection of the corpse is to establish the cause of death and the pathological processes involved. The pathologist strives to acquire reliable information concerning the nature and cause of the disease, and perhaps to investigate the medical procedures used on the patient. The initial autopsy incision opens the entire body in a "Y" shape. It begins below one shoulder, continues under the breasts, and extends up to the corresponding point under the other shoulder. This incision is then joined by another in the midline extending down toward the pubis, to complete the "Y." The scalp incision begins under one ear, extends across the top of the scalp and ends behind the other ear. The organs are removed and studied to the extent of each individual autopsy requirement. It should be noted that the standard autopsy permit form in the Autopsy Manual published by the United Hospital Fund of New York includes, as a matter of course, authorization for "the retention of such parts and tissues as the hospital staff may consider necessary for diagnosis."

Consent from next of kin is required for autopsy. Such consent may be given by the legal custodian of the body who is responsible for the burial, usually the husband or the wife. If there are more than one "next of kin" (and the interpretation of that phrase is elastic) and controversy arises, the hospital may forego autopsy or elect the most amenable relative as "the" next of kin.

In truth, however, it may be fairly surmised that the cause of death is accurately known in most cases, and only rarely is this a medical mystery. From experience with modern medical procedure, it is evident that autopsies are most frequently recommended in order to enable medical students and internes to study and practice by dissection and observation of the corpse. Many articles in medical journals have asserted that recent progress in patho-physiological science has made possible the reliable determination of cause of death without an autopsy. It is now held by many authorities that, with some exceptions, autopsies are no longer considered as vital as they once were.

Nonetheless, it appears that the percentage of autopsies is still considered one of the best indices of the standard of medical practice in hospitals. For this reason the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Hospitals requires the maintenance of a satisfactory autopsy percentage. The United Hospital Fund standard manual urges obtaining consent in every possible case. "Indeed," says the Autopsy Manual, "when permission is not obtained, the physicians in attendance should be expected to account reasonably for such failure."